I often conflate staying out late and partying with making the most of being alive, or even more specifically, I associate it with a subtle form of rebellion against a culture that increasingly wants people to be more comfortable staying inside alone and withering away into consumerism inside of an Amazon-built fortress maintained by a 12-step skincare routine. I know it’s not always this black and white, and perhaps each case is not so extreme, but when I stay out late it feels like one of the only ways I get to be in control of my time and so subtly live outside of the dominant system. It’s not that I would even call myself a party girl, because my finances, work schedule, and introverted tendencies often get in the way. Moreover, I don’t even really have a group of people that I see on such a regular basis that we have a set Friday-night plan (a girl can dream). However, since starting a new relationship, my boyfriend has shown me the art of casually staying out until 4am with your friends, enjoying the company of each other and the city in a way that makes me feel so alive and also really tired at work the next day.

One of these nights out before a workday fell before my roommate and I went to see Daisy von Scherler Mayer’s 1995 cult-classic, PARTY GIRL, at Metrograph. My hungover Sundays usually start with a difficult wake up to a bagel to a burst of energy to a dissociation into flow state where I sell handbags for 8 hours. When I get home I usually just lay in bed and shout to my roommate through the wall until I’ve deemed it an acceptable time to go to bed. On that particular Sunday, however, my roommate and I booked a 9:45 screening of PARTY GIRL at Metrograph, which went against our usual Sunday-night ritual. I feared that I would be doomed to the pain of struggling to keep my eyes open in the theater, and I even had some caffeine in anticipation, because I did not realize the way that PARTY GIRL’s meandering plot would keep me so consistently engaged during its runtime. I loved PARTY GIRL, and I would even go as far as to say that I miss the viewing experience in all of its fullness. With an unforgettable soundtrack that I watched many people dance to, the sensorially engaging colors of Posey’s outfits, and the sporadic narrative, the movie was like a little party itself.

So if it wasn’t already obvious, Here is what I watched at Metrograph last month, and Here are some of my thoughts:

PARTY GIRL (1995) BY DAISY VON SCHERLER MAYER

What immediately stands out about Daisy von Scherler Mayer’s 1995 film PARTY GIRL is that it is a film that was meant to be experienced; it is a spectacle that can be seen and heard and felt. That it was the first movie to premiere on the internet via a live-stream from the Seattle International Film Festival suggests that it is a movie that prioritizes a sense of live-audience interaction.1 Between the diegetic score, the amateur actors that were really part of the scene, the almost tactile costumes, and the on-location shooting, PARTY GIRL not only captures the spirit of a Lower East Side moment that many people can find a version of themselves existing in, but a lot of the message of the movie becomes the experience of viewing it rather than the story itself.2 I watched the theater sway and bounce during the whole movie, because visually, narratively, and sonically, it actually feels a little bit like a party.

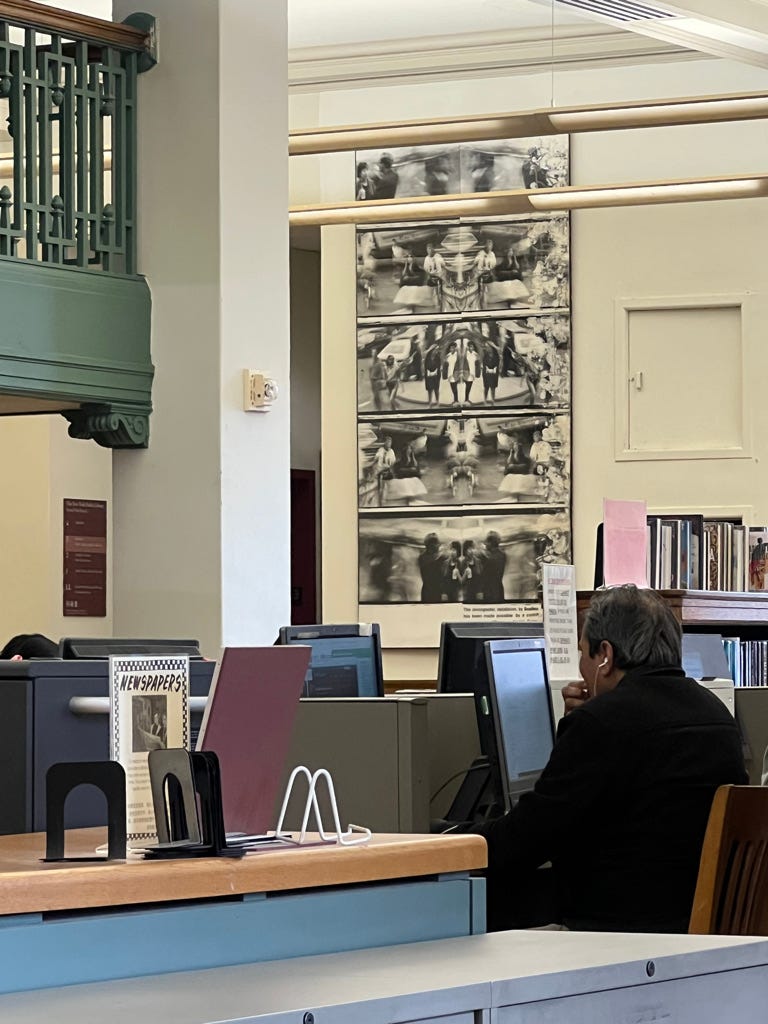

Despite what I just mentioned about this not really being about the story, which is often quite ridiculous and sparse, Parker Posey’s dualities as Party Girl and librarian are not just a charming portrayal but also a hopeful one. In PARTY GIRL, von Scherler Mayer uses particular visual cues to represent the two separate realms that Mary occupies, but throughout the film, as Mary learns to love the library, those two worlds begin to merge. Culturally and in terms of the movie, visually, the librarian and the party girl occupy very different spaces, and von Scherler Mayer draws upon certain ingrained visual codes to indicate that.3 The party girl is fun, sporadic, stylish, and youthful, while the librarian is “matronly”, sexually repressed, orderly, and intimidating.4 In this sense, the nature of both stereotypes is culturally fixed. However, for all of its narrative instability, PARTY GIRL presents a world where Mary can be both. Her transition is not easy, but little by little the seemingly opposed worlds start to make more sense together.

While being both a librarian and a party girl may require some sacrifice from Mary, von Scherler Mayer visually demonstrates that two opposing stereotypes can coexist, and like that she challenges our stereotypical understanding of both–she destabilizes that notion from within.5 While Mary starts dressing a little more conservatively as the film progresses, she still finds time to dance, most iconically when she struts down the table in the library and does cartwheel over a stack of books. In fact, what is most exciting to me about this film is that is suggests that you can be a party girl and you can also love books, and those two ideas don’t have to exclude each other. I suppose at this point the world is filled with party people who also read, but I really appreciated von Scherler Mayer’s visual integration of the two juxtaposed stereotypes. There is a lot of power in being able to accept opposed yet coexisting realities; there is power in accepting the uncertainty of the in between. There is also some power in being someone who likes to hang out and dance who also reads.

Taylor Ghrist, “The Secret History of Party Girl,” Dazed, June 10, 2015, https://www.dazeddigital.com/artsandculture/article/24991/1/the-secret-history-of-party-girl.

Rachel Greenspan, “An Oral History of Party Girl, the Cult Film That Made Parker Posey the Queen of the Indies,” The Wall Street Journal, May 29, 2020, archived at https://archive.ph/20200608135245/https://www.wsj.com/articles/party-girl-oral-history-parker-posey-11591621366.

Marie L. Radford and Gary P. Radford, “Librarians and Party Girls: Cultural Studies and the Meaning of the Librarian,” The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy 73, no. 1 (2003): 54–69, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4309620.

Marie L. Radford and Gary P. Radford, “Librarians and Party Girls: Cultural Studies and the Meaning of the Librarian,” The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy 73, no. 1 (2003): 54–69, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4309620.

Marie L. Radford and Gary P. Radford, “Librarians and Party Girls: Cultural Studies and the Meaning of the Librarian,” The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy 73, no. 1 (2003): 54–69, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4309620.