The Unlikely Companionship of Arrival and Three Colours: Blue

Two journeys in sensorial immersion

Every film lover (me avoiding saying cinephile) has those very special films that mark different milestones in their relationship with cinema, which is in a constant state of evolution. I like to think back to the time that I realized I wanted to study film and dedicate my life to it but had no idea how it would take shape. This was a beautiful period when I had an endless energy to devour and to be inspired; it felt like nothing could ever stop that momentum. There are two films in particular that I associate with that period of what felt like limitless growth: Krzysztof Kieślowski’s first installment of the Three Colours trilogy, Blue (1993) and Denis Villeneuve’s Arrival (2016). These are two very widely acclaimed films that have already inspired lots of discussion, to the point where I am not sure how much I have to offer to the conversation, but what is most important here is that they mark a turning point in my young relationship to movies, and my guess is I’m not alone in that. They are kind of those movies, and while vastly different, they have a lot in common, not just because of the way they left me in tears in my theater seat, but also because of how they reveal the sensorially immersive power of cinema.

Kieślowski’s Three Colours: Blue is a multisensory experience and uses the great immersive potential of the medium to connect sound, color, and memory. The film starts strong and is pretty immediately immersive with its impressionistic approach to understanding the story’s traumatic catalyst: a car crash which kills the protagonist, Julie’s, husband and daughter. The crash is told in fragmented pieces: a close-up of a tire, a hand shooting out of a window, blurred traffic in a tunnel, which work together to form a greater whole. Kieślowski’s gestalt, pointillistic opening sets the tone for the relentless (at times ostentatious) subjective perspective of the film; in Blue it’s not as much an invitation into Julie’s world as it is a forceful entry.

Moreover, the camera’s interaction with its subjects is intimate and intentional, and it is Kieślowski’s use of the special abilities of the kino-eye, the gaze specific to the camera, that establishes an atmosphere of subjectivity, or at least the illusion of it. For example, when Julie talks to the doctor in the hospital, Kieślowski does not use a standard POV shot; instead, the conversation is portrayed through the reflection in Julie’s eyes. He experiments with what a faithful representation of reality may look like and calls into question the medium itself for both its mirror-like qualities and its limitations.

Not only does Kieślowski immerse viewers visually, but he also does so sonically; in fact, the two often operate symbiotically. The sound in Blue is intrusive, but it is often natural, or diegetic. Like he does with the visuals, Kieślowski focuses on the small to the point where the sound of echoing footsteps through a hollow house take on a life of their own, for example. In that sense, he demonstrates the various dimensions of sound, like when Julie listens outside of her apartment to a man get chased down the street until she slowly hears him enter her building in order to highlight cinema’s power to selectively tell a story using its sensorially immersive qualities.

However, the boundaries between diegetic and non-diegetic sound are often blurred, which ultimately connects the senses and brings us closer to her Julie’s inner world. She runs her fingers across a sheet of music and she hears the sound of a symphony, which is also the score of the movie. She eats a piece of her daughter’s blue candy not to eat it but to experience it, and the grief-filled crunches pierce through the screen. The one belonging that she keeps of her daughter’s is a blue glass chandelier whose reflection is captured so beautifully on Julie’s face, and as audience we are cued to associate a sound and a color with Julie’s grief as if we are present in the multisensory experience that it is to remember. Kieślowksi takes advantage of film’s ability to microscopically look at the almost imperceptible to experiment in immersing the senses, which cues us into Julie’s grief on a deeper level than just the sympathetic viewer.

While Kieślowski demonstrates the power of cinema to engage the senses on the scale of a relatively small art film, Denis Villeneuve achieves a similar effect working with an entirely different sensibility in Arrival; he instead does it both subverting but mostly upholding the traditions of a Hollywood Blockbuster. The film opens with the beginning of a life, and as Louise’s baby daughter cries we are immediately told to value sound during the viewing experience. Louise teaches a lecture on language and sound as the news of the 12 ships spreads, and Villeneuve introduces an all-consuming, otherworldly score by Johann Johannsson. That baby’s cry as it enters the world is also our beginning, and Villeneuve invites us to teach us and immerse us with the basic filmic principles of subjectivity.

Much like Kieślowski, Villeneuve emphasizes the idea of sound as something that can unlock a subjective experience as Louise sits in the helicopter and puts one headphones to block out the sound and introduce herself to Ian, and in that moment it is established that we hear what Louise does. Later, on the base, Villeneuve presents the act of putting on a hazmat suit so intimately that through sound we can even feel the texture of the suit, and we can hear every breath Louise takes. These diegetic sounds start to form part of the non-diegetic score until it is hard to tell them apart, and it seems like the Johannsson’s score could even be radiating off of the ship. This provokes both the feeling of intimacy and a sense of awe in the viewers that overcomes the senses more than it engages them.

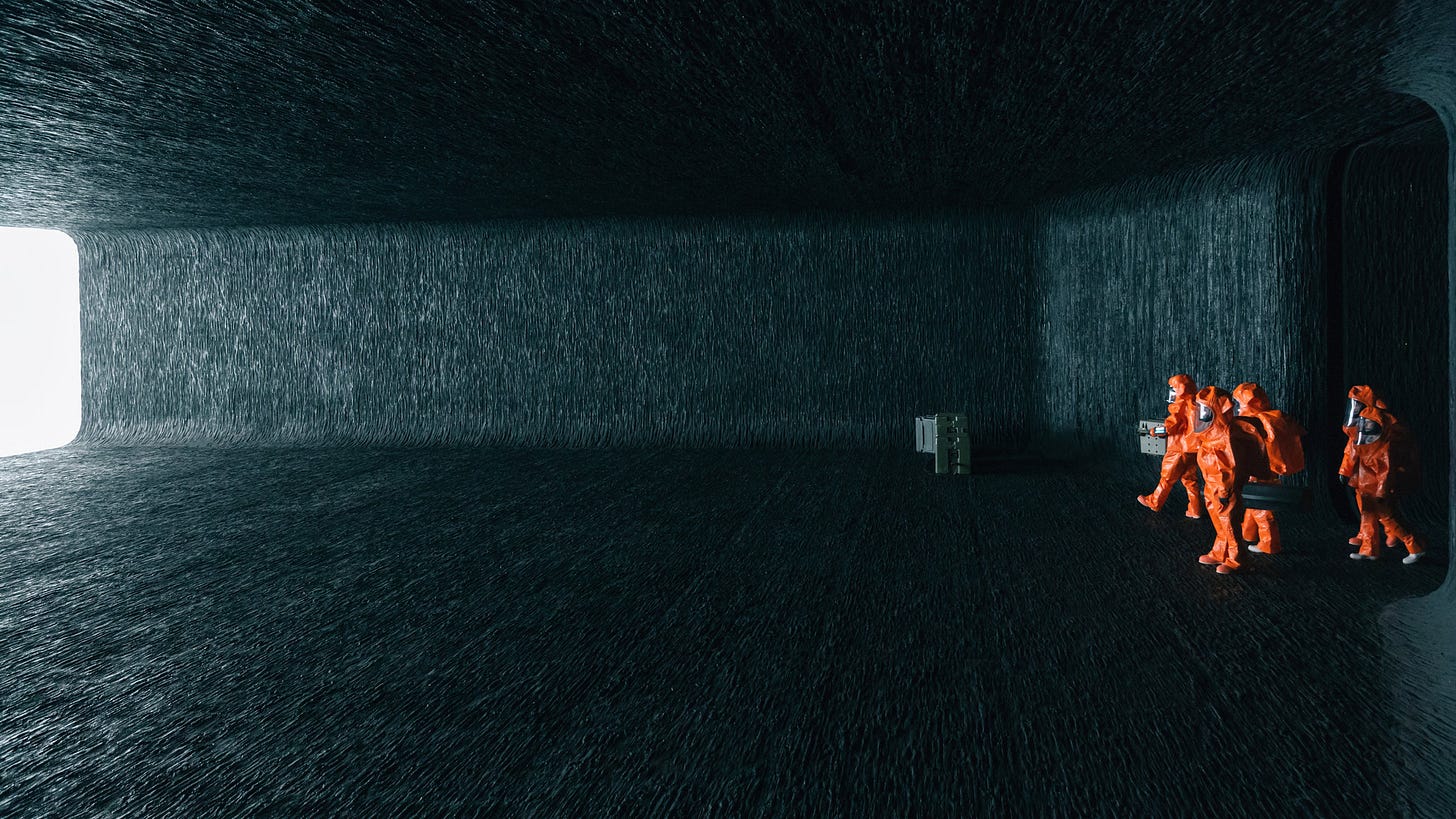

Like Blue, Arrival is also particularly visually stimulating and engages the multifaceted nature of the medium. While the sound of the heptapod’s language is called into question first, it is actually a visually interactive language that does not rely on sound at all. When Louise and Ian interact with the creatures and learn their language, Villeneuve calls upon the medium of film as a space. The inside of the ship very literally echoes the appearance of a movie theater with the audience sitting in the dark looking at a big bright screen they are seemingly unable to penetrate. He presents cinema as a space that is somewhere in between the audience and the screen; it is somewhere unknown, somewhere pedagogical, it is a space of interaction.

Further, light and dark are starkly juxtaposed throughout the film, and in the ship, the aliens are presented in the light while Louise and Ian are in the dark, a very literal depiction of their range of knowledge, which mirrors that of the audience. Villneuve suggests that the screen is a barrier, but he still insists on inviting the viewer in to come as close as possible. It was not until the credits rolled and I took a deep breath that I realized how close I had actually gotten. I remember staring at the screen in tears as I sat and let the film release inside of me, because that is what Arrival does. It injects itself into you using Hollywood conventions and the mainstream priority of continuity in film. It is immersive in the way it inundates, overwhelms, overcomes the senses.

Denis Villneuve’s Arrival and Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Three Colours: Blue reveal cinema’s multisensory nature, and the two work together in unlikely ways. Before I could even articulate most of this, I experienced these two films in my body, which now marks the beginning of a pivotal chapter in my relationship with film. At this point I can’t help but think of the two of them together, they’ve almost become intertwined to me, both for the way they complement and foil each other. These two films cloaked in monotonous grey hues and entrancing scores are rooted in their connection between sound and repetitive visual cues to immerse the senses of the viewer and allow them to make connections that feel organic.

They employ similar tools of the medium to explore themes of life and death, grief, and human connection; however, they use vastly different rhetorics. While Blue is an independent experimentation that takes advantage of practical resources for the sake of experimentation, Arrival, despite subverting some expectations of the typical sci-fi thriller, is very much a baby of big Hollywood resources. While Blue disrupts, Arrival conforms. Their distinct visions of immersion remind me of how vast the medium is while also being unified by some haunting feeling that leaves me crying in cinemas sometimes. This was the beginning of my inspired cinema cry.

I invite you to a double feature :)

and hell yea I listened to the Arrival score while I wrote this

References:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Three_Colours:_Blue

https://www.criterion.com/films/27731-three-colors-blue

https://www.indiewire.com/features/general/three-colors-trilogy-kieslowski-review-1234739182/